Bill Cobb Jr. was in high school the first time he heard someone say his family was going to lose its Bonita Springs property. It was the late '90s, and Cobb and his father were attending some of the first meetings with representatives from the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD), which wanted the family's Harrell Avenue property for flood relief.

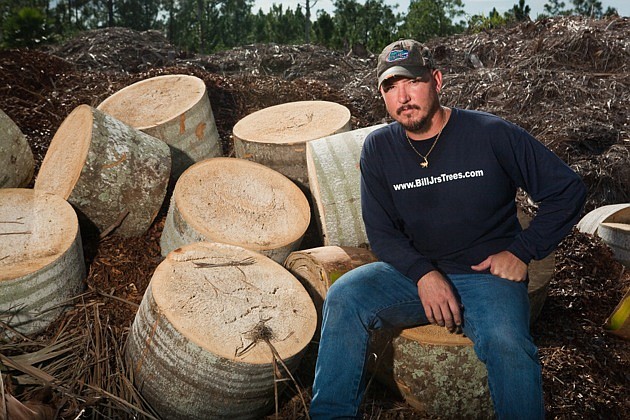

More than a decade since, Cobb, now an entrepreneur who owns the five-acre property with his sister Christina Kunz, is finally losing it to the district through eminent domain. The district recently acquired the property, and he has received a notice evicting his tree-service company from the property on Nov. 21. Left with few real estate alternatives, Cobb says the eviction will put him out of business. As he looks for another job, Cobb points to his family's lengthy battle with the water management district as a case of eminent domain run amuck.

The project, known originally as the Southern Corkscrew Regional Ecosystem Watershed (So. C.R.E.W.), stems from a major rainstorm in 1995 that caused a 100-year flood. The rain ultimately displaced some 1,700 residences near and including the Manna Christian Missions RV park on Bonita Beach Road for weeks.

To reduce the impact of future flooding, SFWMD conducted a watershed study, which determined the agency should acquire a large area of east Bonita Springs from Bonita Grande Drive to the Collier County line for water retention. At the time, the 4,760-acre property housed some 50 single-family homes and a number of businesses.

Following the study in 1997, the district started buying parcels in the So. C.R.E.W. from voluntary sellers. After the district had acquired 1,536 acres or 32.9% of the total project, the SFWMD board passed its first eminent domain resolution. In April 2002, SFWMD went to court to ask a judge to allow it to take a portion of the targeted property through eminent domain.

But in what is proving a pivotal decision, the Cobb family and a number of So. C.R.E.W. property owners who were not targeted in the suit entered the case to fight the taking. They hoped to argue that the taking was not for a reasonable public purpose, that a full property taking was unnecessary to relieve flooding and that the footprint of the project was too large.

They lost, and the judge granted the eminent domain taking.

Unfortunately, when the property owners lost their case — even those whose property was not being taken at the time — they effectively gave up most of their avenues to dispute an eminent domain taking for their own properties, when the time came.

Instead of requiring SFWMD to defend why the property was being taken, the district would only have to prove that a proper market price was being paid for the property. SFWMD could even take ownership of the property by just putting up its assessment of the value of the property; any court case challenging the value of the property would happen later.

That's where the Cobb property and most of the other holdout property owners have sat for the past nine years — a virtual limbo, where the property is unsellable and ready for the taking at the whim of SFWMD.

“Over the past 15 years they've made our property pretty much worthless by the things they've done,” Cobb says. “They did 80% of the acquisitions eight years ago, so why then haven't they taken out the power polls or the culverts [from around my property]? They haven't done anything to complete the project. They aren't even keeping people out. The area's become popular for off-road recreation.”

In May, SFWMD finally sued to condemn the Cobb family property. Cobb, through Jackson Bowman of Brigham Moore LLP, who is also representing three other property owners in the area, has filed a counter claim to the eminent domain suit arguing for blight damages. The suit says the threat of condemnation and checkerboard acquisitions have had a negative impact on the property, depressing its uses and value and causing an inverse condemnation (a government taking without fair value compensation).

Much of the delay comes admittedly after SFWMD ran out of money for the takings, which is not unusual or illegal, according to Scott Johnson of Holland & Knight, who is not involved in the case.

“Unfortunately it happens, where an authority, through no fault of their own, runs out of money after they start the process for the taking,” says Johnson, an Orlando attorney with 35 years experience dealing with Florida eminent domain law. “Money troubles are not at all uncommon for condemnation authorities. We've seen this with [the Florida Department of Transportation] for land to expand the interstates.”

The legal distinction, Johnson says, is that the legal authority hadn't actually filed an order of taking to acquire the property before May. He says steps that designate the property for a future taking are generally legal because government agencies are allowed to take planning steps prior to a taking.

Bowman argues in this case the delay was excessive and has depressed the value of the land. Johnson says the longest taking he has experienced was five years.

“It was unfair to the folks that owned the property out there to just make them sit,” Bowman says. “With the takings, the resolutions [from the district board directing the taking] came in October or November or January 2002. The statute that the Legislature adopted directing the district to acquire the properties was adopted in 2000. Plus, they waited until the [real estate] market is in the toilet to do their taking.”

For Cobb the taking seems patently unfair. SFWMD designated his property and others on the north side of Bonita Beach Road for taking while the south side of Bonita Beach Road was developed into several large residential communities including Bonita Bay from The Bonita Bay Group and the Palmira Golf & Country Club. In addition, SFWMD has removed property abutting Bonita Beach Road two miles to the east of Bonita Grand Road and north to Kehl from its acquisition plans. The district says it achieved the property it needed for the Imperial River flow way without those parcels. Cobb and others say the district removed that portion of the property because the district couldn't afford to buy it.

Cobb isn't the only property owner in the area calling the boundary areas capricious. In another lawsuit, brought by Bowman, property owners Marian Taylor and her son Paul Taylor Jr. accuse the district of a de facto taking of their property. The Taylors, who own three homes located north of Bonita Beach Road fronting the Imperial River, were originally included under the So. C.R.E.W. plan. The homes were never acquired and in 2009, SFWMD announced it would exclude their property from the So. C.R.E.W. plan.

The Taylors say they tried to sell the properties four times between 2005 and 2009 with no interest because of the district's threat of condemnation. In addition, the district removed the Orr Road/Kent Road Bridge over the Imperial River and culvert, which now limits the Taylors access to their property.

The court case states “Plaintiffs have been left with properties that are unsaleable (sic) on the open market: more susceptible to extraordinary flooding; undevelopable for any other use than that to which it is currently put; and unable to be re-financed.”

A media relations official for the district declined to answer questions related to the project, which has since been renamed the Critical Corkscrew Regional Ecosystem Watershed. In a statement, SFWMD emphasizes the significant benefits of the project, including restoring wetlands and the historic sheet flow of water, improving regional flood protection and drainage and increasing water storage and aquifer recharge capability.

The district says to date it: “has acquired approximately 97% of the more than 4,100 acres of land needed for the project. With the courts affirming the public purpose and necessity of the project, all of the properties were either acquired from willing sellers or settled out of court.” Further, it says its restoration progress also includes the clearing of exotic vegetation from 2,560 acres, removal of roads and plugging of agricultural ditches on 640 acres and improvements to the Imperial River flow way.

“The District anticipates an acceptable agreement with the remaining property owners to acquire the final acreage needed for the restoration project,” the statement concludes.

As of January 2009, the district had invested $27.4 million to convert the land and the U.S. Department of the Interior contributed another $7 million to the restoration effort.

For his property, Cobb received the district's appraised value of $70,000, which he split with his sister. The Lee County Property Appraiser puts the assessed market value of the property at $25,000, which is unchanged since 2007. However the appraiser's market value of the property was up only slightly from the $19,500 it has recorded every year prior from 1996 to 2006.

Although he is hopeful that the countersuit will lead to a higher value for his property, closer to his personal assessment of around $325,000, Cobb is not optimistic about his company's future real estate prospect, particularly because of the company's unique zoning needs.

“At a minimum I'm going to have to pay to dump [our horticultural waste] somewhere, which is going to cost my customers more money,” he says. “This has taken so long now that the properties just aren't available in Bonita Springs.”