- October 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

The potential reach of artificial intelligence is deep — and can even penetrate the seemingly benign job applicant screening and hiring process. A process that, in many ways, screams for automation, especially in large organizations.

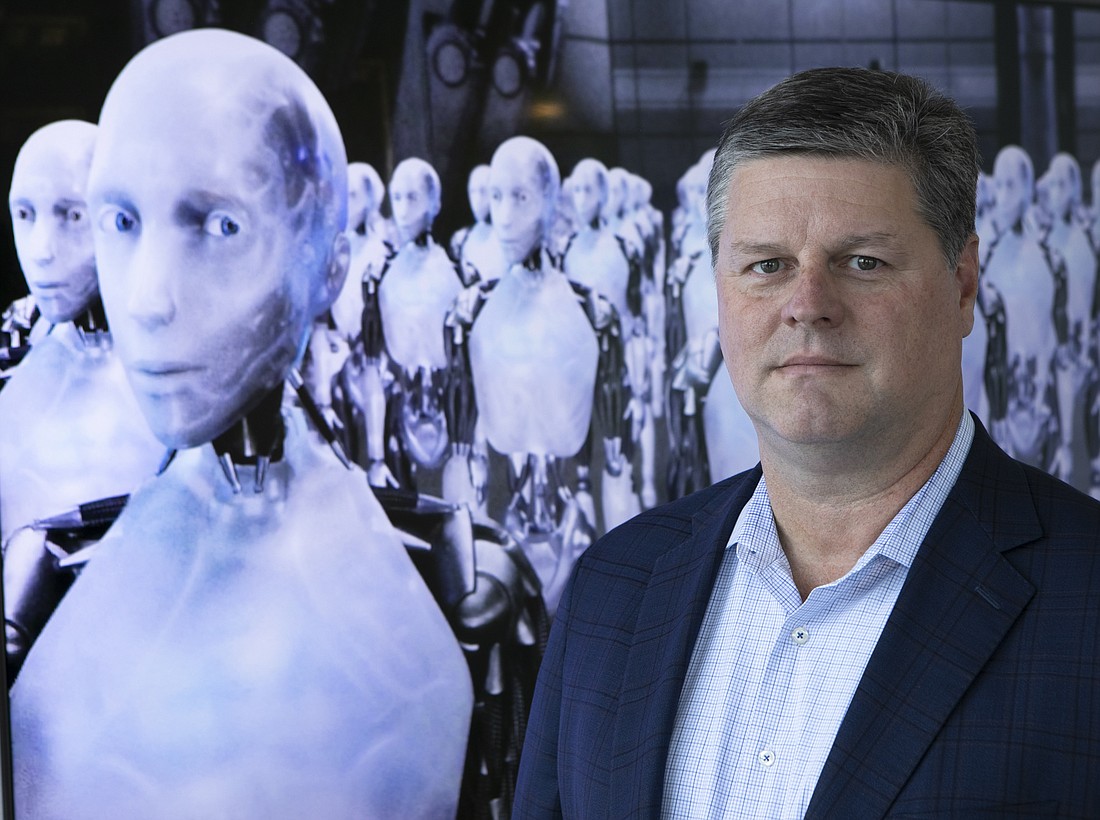

But Tampa attorney Kevin Johnson, an expert in employment law, says employers that use advanced AI-based tools to efficiently filter candidates for open positions should be aware of the legal risks. And those risks are plentiful.

“A lot of employers are starting to wake up to the potential of AI and trying to evaluate whether they should be using it in their workforce,” says Jackson, a partner at Johnson Jackson PLLC in Tampa. “There are already companies out there that are producing hiring applications that incorporate AI. But the question becomes, ‘If I’m using that process, as an employer, is there discrimination that can creep into it anywhere?’”

The potential for AI-related legal peril has become so great that the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission recently issued guidelines for employers designed to help them avoid running afoul of the Americans with Disabilities Act and other anti-discriminatory measures. The EOOC’s guidance, Jackson explains, says that even the best-intentioned employer can unwittingly discriminate against certain job applicants simply by using chatbots and other advanced data-collection technologies that don’t make accommodations for all users.

“If you are relying on an AI-based application, it may not be the AI that causes a problem,” he says. “It might just be the input tools that you're using to interface with the AI. So, for example, if your application requires someone to type on a keyboard, or read a computer screen, and you haven't made that accessible to visually disabled users, or physically disabled users, that can be a problem.”

That’s a relatively “low-grade problem,” and not difficult to remedy, Johnson says, but the real danger comes from an AI program’s “decision-making framework.” An AI or other algorithmic decision-making tool might screen out a disabled applicant who could perform the essential duties of a job with a reasonable accommodation — and that is unlawful.

“The employer’s obligation to provide reasonable accommodation is not just once you’re hired,” Johnson says. “It also extends to the job application process itself.”

He uses the example of a job application question that asks whether the applicant can lift 100 pounds or stand for 75% of the time that they are at work.

“The applicant has to write, ‘No.’ And that's essentially their only choice,” Johnson says. “And then, if you automatically strike them, you haven't given them the opportunity to say, ‘No, but I might be able to do this job with reasonable accommodation.’”

The EOOC says there are many other ways AI can illegally screen out qualified candidates. It might reject an applicant because of a gap in employment, even if relatively brief. But, according to the EEOC website, “if the gap had been caused by a disability (for example, if the individual needed to stop working to undergo treatment), then the chatbot may function to screen out that person because of the disability.”

Johnson says there’s a simple way to mitigate, if not eliminate, the risk of discrimination: “You’ve got to build ‘clues’ into your interface to say, ‘If you need reasonable accommodation, answer the question “yes” if that reasonable accommodation could be provided, and then we’ll figure it out once the offer is extended.’”

Employers also need to be aware of their potential liability in discrimination claims involving AI. According to the EOOC, “an employer may be held responsible for the actions of other entities, such as software vendors, that the employer has authorized to act on its behalf.”

As AI increasingly shows up in hiring processes, Johnson says the EOOC will be looking to “make an example of” companies that, intentionally or not, use AI-powered screening tools that discriminate against certain categories of job applicants. Thus, employers need to be asking questions of their software vendors.

“We’re trying to raise awareness and having conversations with clients,” he says. “Those who are developers, and those who are users, we want them to understand the risks. When you purchase one of these things, you have to look at your contractual allocation of responsibility and how you're going to cooperate with each other if it gets challenged.”