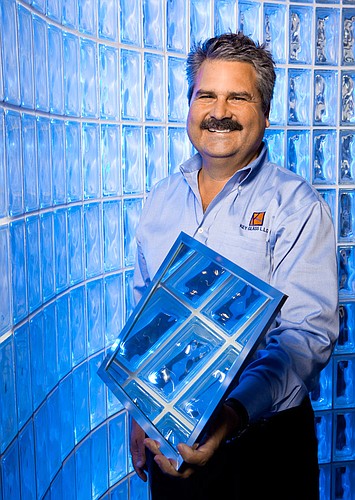

When Greg Burkhart launched a window-installation firm during a recession — the one in 1992 — his inner circle thought he was a tad mad. Crazier still: He's now pumping money into the company to outlast the recession.

Greg Burkhart's original daily recession survival plan consisted of three basic necessities: 16-hour workdays, a loaf of white bread and a package of bologna.

The double shifts were to keep up with the workload at the glass installation company he had just co-founded with his wife, Sheril. Even though the construction industry was struggling, Burkhart was still the do-everything man, from bidding jobs to installation to negotiating contracts and customer service.

The white-bread-and-bologna sandwiches were how he sustained himself during his marathon workdays.

This was back in 1992, not the current recession. Burkhart, then 37, had just launched Bradenton-based Key Glass. He had next to no credit, so he had to pay cash for all deliveries. “And we couldn't get a job worth more than $3,000,” says Sheril Burkhart.

As if starting a new firm wasn't challenging enough, Burkhart was also recovering from his previous business entity: Working for his brother-in-law's window company, which was shuttered soon after filing for bankruptcy. “Christmas and Thanksgiving weren't too fun,” Burkhart says of those days.

But the Burkharts persevered through the early-stage struggles.

So much so that Key Glass is now in some rare company: It's still growing, albeit at a slower pace. Annual revenues were up 10% in 2008, from $6.5 million in 2007 to $7.2 million, good enough to be ranked 48th on Glass Magazine's 2009 nationwide list of the industry's top-growth firms. Burkhart projects Key Glass' sales will be flat or a slight bit down this year — its first non-growth year ever.

The 35-employee company is strictly a commercial construction window seller and installer. Clients include many of the area's top construction firms and projects are diverse, from several Beall's and Publix stores to schools in Manatee and Sarasota counties and car dealerships and banks. The company works mostly on the Gulf Coast but has gone as far south as the Keys and as far north as Jacksonville.

There aren't too many other construction-based subcontractors on the Gulf Coast that can boast of growing, or even flat, revenues these days. “If we break even this year, we will consider that a victory” says Sheril Burkhart, who runs the financial side of the company.

Greg Burkhart, now 55, attributes Key's ability to survive the recession to, well, a few keys: He saw the downturn early on and began to look for new markets and adjusted prices before his competitors; he has recommitted the company's sales effort to making sure customers get more for less; and, in his riskiest move ever, put $300,000 back into the company late last year by buying new software and glass-cutting equipment.

“It all comes down to can you do it faster and can you do it better,” Burkhart says of the current market realities. “That's what we sell.”

A good view

The Burkharts have an edge in meeting those goals: a family history encased in glass.

Sheril Burkhart's father was an executive with Guardian Glass in suburban Detroit in the 1970s, working closely with founder William Davidson in a successful turnaround effort at the company that sold windows to automakers. Davidson eventually owned the NBA's Detroit Pistons and the NHL's Tampa Bay Lightning.

Greg Burkhart, meanwhile, initially planned to pursue a career in engineering, the subject he studied while attending college outside Detroit. But in the 1970s, moving to Florida to help his wife's brother run a window company seemed like a better gig.

And it was, for a little while. Business at the company, Tru-Vue, was good in the 1980s and Burkhart was getting good on-the-job experience. At one point he moved to Orlando to open and run a sales office there.

But Tru-Vue, the Burkharts say, grew too fast and by the late 1980s was having some financial challenges. It later filed for bankruptcy, a heart-wrenching yet valuable experience for Burkhart. “I think it's a blessing in disguise to work for a company with financial problems,” says Burkhart. “It teaches you what not to do.”

Burkhart took those lessons to Key Glass, although at first, people around him questioned the wisdom of starting a subcontracting construction business when the industry was faltering. Burkhart remembers a few people in the industry were frank with him, including one who told him point-blank: “Your chances of survival are pretty slim.”

The Burkharts nonetheless launched the business, starting it from their living room. The first lesson they learned is an entrepreneurial staple: Do one thing and do it well. “Tru-Vue tried to be a one-stop shop,” says Burkhart. “But I found you are better off sticking to a niche.”

That niche was commercial construction — but not including condo work. Burkhart consciously stayed away from that segment in the 1990s and earlier this decade, both for its boom-and-bust risk and the litigation factor.

Says Burkhart: “I didn't want to get into the legal defense game.”

Key Glass continued to grow, in sales and size. It moved from the Burkharts' home to several offices to its current home in a Bradenton industrial park, on land the firm bought in 2000. (See related story).

The family connection has grown, too: The Burkharts' son Justin joined the business back in the boom and initially worked for a new shutter division. As work slowed in that unit, however, Justin Burkhart has shifted to more traditional window work. He's currently one of the project managers at a renovation of the Sarasota Yacht Club.

'Soul searching'

Despite Key Glass' ability to navigate the recession with only a few dings thus far, there are looming challenges.

For starters, the field is as competitive as it has ever been, as dried-out residential window firms have been creeping into commercial work. Another challenge, one faced by contracting firms up and down the Gulf Coast, is pricing.

Burkhart, for example, says he has to lower prices by as much as 30% in some cases just to win a job.

But late last year, Burkhart set out on a refreshingly counterintuitive attack plan: to outspend the recession.

The plan included buying a new glass fabrication machine that could be quicker and more precise with fitting and glazing windows, an integral part of the pre-installation process. That machine cost more than $200,000, a risk that gave Burkhart serious pause. “There was a lot of soul searching going on,” he says.

Burkhart then reinvested in other parts of the operation, such as buying a new aluminum saw and upgrading the pre-glazing machines. The goal was to make products faster and better.

Now, says Burkhart, what were once week-long jobs are completed in two days. And what was previously a 20-minute cut job can now be done in three minutes. “The products we are producing today are far superior compared to six months ago,” adds Burkhart.

Finally, in March, Key Glass spent money on something it hasn't done in its 17-year existence: It hired a marketing and advertising firm.

It was another decision the Burkharts agonized over, since they had always relied on word-of-mouth and referrals to generate business. The company ultimately settled on Sarasota-based Baskerville Advertising to lead its new branding and ad campaign.

Burkhart is confident his risk and expenditures will pay off for Key Glass, both in terms of gaining market share during the recession and for gaining sales growth when the downturn ends. And he adds that his spend-it-to-make-it strategy has already paid dividends in at least one essential way: Employee morale.

“Investing in your business is important,” says Burkhart. “It helps charge up employees and keep them positive.”

'A Bureaucratic Bottleneck'

By the accounts of many in Manatee County business circles, the new regime in the county's building department is a drastic improvement over the not-so-good-old days.

Problems are dealt with in a timely way, and the permit process, for the most part, no longer feels like one long dentist visit. But where was all this harmony in 2007, when Greg Burkhart wanted to build a new headquarters in the county for Key Glass, his fast-growing commercial construction window installation firm?

“Here was a company that wanted to grow and be progressive,” says Burkhart. “And the county was like, whatever, we don't care.”

Burkhart's story was all-too familiar in the boom and through most of 2007. He bought one acre next to his current 9,000-square-foot building, with the hope of constructing a 20,000-square-foot complex that could serve as an office, fabrication plant and storage facility. He planned to spend at least $1.5 million on the project, in the Manasota Industrial Park.

But the county's bureaucratic bottleneck killed Burkhart's plans. He estimates he spent $50,000 to $80,000 in engineering and architecture fees to get the land ready for permits. “The bank was ready to loan us the money,” he says. “We were ready to go.”

Not so fast, the county told him. Some questions and delays focused on the minutiae. Burkhart, for example, recalls a county official asking several questions about where the on-and-off switch was going to be for the sprinkler.

Burkhart and Key Glass eventually obtained a building permit from the county — 14 months after buying the land. By then, in the spring of 2008, the economy had turned and the company decided to hold off on building a new headquarters. Burkhart instead bought the 8,000-square-foot building across the street for about $500,000 and moved some of his operations there.