- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Dean Saunders and his wife Gina were driving on Highway 50 from Orlando to their home in Clermont one day when he realized something.

This was in the early 1980s, back when the 25-mile or so trek from the city to the small central Florida town was a drive in the country. The massive car dealerships and what seems like mile after mile of development didn’t exist back then.

It was rolling hills in those days Saunders says. “Green, lush, rolling hills.”

“I remember saying to my wife,” he says, “‘This will all be houses one day and I'm gonna hate that.’”

And he was right. On both counts.

Today Clermont, in Lake County, feels like an extension of Orlando as a continuous strip of growth connects the two and has transformed the quiet rural community of Saunders' childhood into just another suburb. There were 104 people in his graduating class, he says. Today there are three high schools.

That early realization set him off on a career path that has led directly to the conversation of millions of acres across Florida. He did this by helping create what became the state’s conservation easement program, which allows property owners to sell their development rights to the state or nonprofit land trust in order to both capitalize on the land and continue to work it. This while helping protect the natural resources on the land.

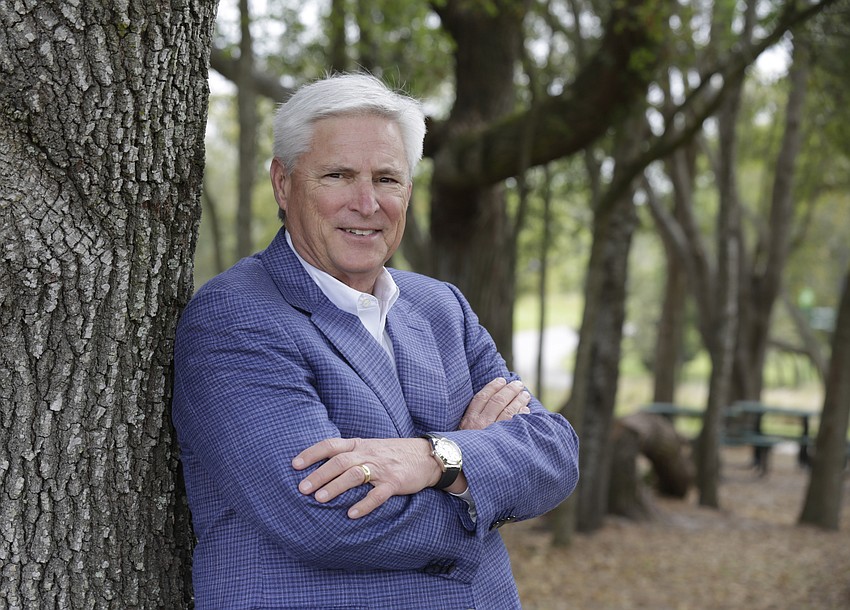

Today, at 64, Saunders runs the Lakeland real estate firm that bears his name: SVN Saunders Ralston Dantzler. It is one of the largest land dealers in the state handling $467 million in sales volume last year.

He founded Saunders Real Estate in 1996 after serving the Florida Legislature for four years, representing Polk County in the House. In 2010, he teamed with Gary Ralston and R. Todd Dantzler to form a sister company, Saunders Ralston Dantzler and eventually merged the two companies.

The firm has 23 employees and three additional managing directors. It went under the SVN umbrella in 2020.

Saunders, whose son Trent and son-in-law Tyler Davis work at the firm, says he has no immediate plans to slow down.

Sure, he hunts a little more than he used to and, as a successful businessman and former state legislator, has the prestige that comes with age and with position. But he likes to work.

And if you are a Floridian who believes in protecting the state’s dwindling land from development, that should make you happy.

Last year alone he brokered the sale of 28,322 acres in conservation easements. The transactions totaled $67.6 million.

“You know,” he says when asked about his future, “I'd like to keep protecting some of the farmland from being developed so that we can all enjoy it and keep this place agriculturally productive. And we can all have green space to enjoy.”

Saunders came upon his love of nature, well, naturally.

Growing up in Clermont, he was a Boy Scout and through high school loved being in the woods, camping, hiking and fishing. He eventually earned the rank of Eagle Scout.

He has maintained that passion for the outdoors his entire life and fostered it in his children, who he took on camping trips at public parks and with friends when they were growing up.

When his fourth child was born, she developed asthma. One night when the family was on a camping trip, she had an attack at 1 a.m. and they had to drive 45 minutes to his parents to get her a breathing treatment.

It was a terrifying experience — and it wasn’t too long after that the way the family camped changed.

They were on a trip when they saw an RV show was going on at a nearby mall. “We said, for kicks and giggles lets go check out these out. Two days later, we drove off with a new mini Winnebago.”

It was a Class C, Saunders says, one of those RVs with the cab over the truck. And from that point on, they travelled all over, visiting national parks and taking historically-themed vacations.

He and Gina are on their fourth RV now, an American Eagle Heritage Edition that to the non-RVers seems more like a bus than a camper.

Saunders had already developed another passion by then. Hunting. Particularly turkey hunting.

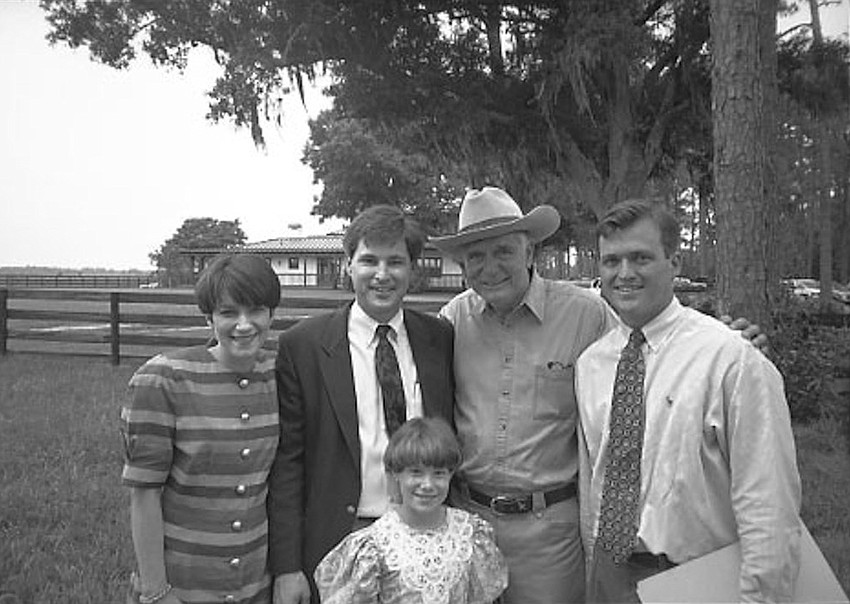

That was before the kids came along, in the years after he graduated from the University of Florida and went work for Lawton Chiles.

Chiles, then a U.S. Senator and later the state’s governor, was really big into the sport of turkey hunting and Saunders just took to it. In fact, when speaking with the Business Observer in early March he was packing to go on a hunting trip.

“Again, it was just another way to be in the woods,” Saunders says.

Saunders began working for Chiles in 1983.

Saunders graduated from the University of Florida the year before with a degree in fruit crops, food and resource economics and gone into agriculture, working for Golden Gem Growers, a citrus co-operative.

Chiles, a Democrat, was looking for an agricultural liaison to help him with ag issues and wanted to hire “somebody who's a cracker,” Saunders recalls Chiles' aid, Charles Canady, told him. The senator wanted someone who enjoyed politics and knew the industry. (Cracker was used as a colloquial term, meaning a Florida native.)

Saunders had been active politically while at UF, serving as president of the Student Senate. Someone from the university had recommended him for the job, Canady told Saunders.

Working for Chiles changed the direction of Saunders' life immediately and in, some significant ways, changed the future of Florida.

Over the course of a decade Saunders worked for Chiles in the U.S. Senate and then the governor’s office, serving as an agricultural liaison, special assistant and director of external affairs before running for office himself in 1992.

“It was clearly a paradigm shift for me because I never saw myself going into any political thing,” says Saunders, a Democrat when he held elected office. “You know, I had the notion then that those kinds of jobs go to people that are big donors.”

His family was civic minded and involved, but this was a whole other level.

Not long after joining Chiles, Saunders and Gina took that fateful drive from Orlando to Clermont.

Florida had suffered several years of deep freezes that decimated the citrus crop, killing hundreds of thousands of trees. Lake County alone, he says lost 120,000 acres worth of trees in a single night one freeze.

The couple had been married about a year at the time and when they made the drive the road was lined by “these dead, gnarly trees.”

“It looked like something from a dystopian novel, just gnarly trees everywhere,” he says.

That’s when he shared with her the fear that the land would one day become all homes.

And that’s when the idea was born. “I had no context other than just this idea. What if we could pay (landowners) not to develop it? They could still own it, but it wouldn't be developed. That way, maybe they'd replant. Right? They could stay in agriculture.”

Armed with the concept and the idea, Saunders began what turned into a years long effort to turn what would become conservation easements into a reality. It involved bringing two side together who were historically at odds — landowners and environmentalists. It involved convincing colleagues to take a chance by buying the development rights from farmers rather than the state buying the property.

He took the idea to the Florida Farm Bureau which he had worked with at one point, but the organization thought it was too avant-garde.

He argued that if the state bought the land outright, it would have to allow residents on it, putting the resources at risk. Plus selling it would remove the property from the tax rolls.

And, what if someone came into office one day that wanted to sell off the land? Or the state found itself in economic straits and the bidders began to line?

Sure, he says, there is a place for the state to buy land but buying the development rights is a better, long-term solution.

Selling the development rights, he firmly believed, was the answer.

The question was, how would he prove it?

Enter the Green Swamp Authority.

The Green Swamp Authority was the test case that would prove the theory Saunders had been espousing would work in the real world.

The idea behind the 1994 piece of legislation was to create the authority in order for it to buy the development rights from landowners in the Green Swamp, a 322,690-acre area in Polk, Lake and Sumter counties that in 1974 was designated as an Area of Critical State Concern by the state.

It was both a way to conserve that land and a pilot program.

Saunders wrote the legislation proposed in the House and was its biggest proponent.

Eric Draper, a well-known advocate for water and land conservation and Everglades restoration, says he remembers Saunders at the time as “just hard working, really hustling, persuasive and unyielding in (his) intention to get that green swamp legislation” through.

Saunders got Rick Dantzler, now COO of the Citrus Research and Development Foundation and then a state senator, to introduce the bill in the senate.

He did. But on one condition. Saunders would have to sell it to senators himself.

Saunders, who started as a salesman at eight years old selling tickets for a Rotary pancake supper for his father by going door-to-door in Claremont, did just that.

The legislation passed and the authority, according to press reports at the time, got $30 million to buy land over a three-year period.

And it created a model still in use 30 years later.

According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, 140 conservation easements have protected more than 262,000 acres statewide since the late 1990s

In May alone, a dozen landowners have sold the conservation easements on 38,848 acres of their agricultural property to the state of Florida for $97 million. Saunders brokered the sale of 18,427 of those acres, in deals totaling $45 million.

“I did have a role in it. But make no mistake about it, this was Dean's creation,” Dantzler said on a panel during February’s Lay of the Land Conference in Lakeland that marked 30 years of conservation easements

“All of us who had the privilege of serving hope that there will be something that we do that has significant impact and import for the state. And this was certainly one of those. But don't give me the credit for it. That credit lies with Dean.”