- October 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

You can say we were guilty of media hyperbole and doom-sdaying. But we’ll categorize it as the story is still unfolding and not in a good way.

About this time last year, we wrote that “rising property insurance rates are on the verge of popping Florida’s housing bubble and the economy — all because of lawsuits.”

We quoted an insurance analyst who spent six months studying Florida’s property insurance industry saying: “Florida’s P&C market is in a free-fall collapse. This market is going to fail.” We quoted a judge who tried thousands of insurance cases and told us: “The sky is falling. It is a financial crisis for the citizens of this great state.”

And we made a list of predictions of what would occur if Senate Bill 76 did not pass. We predicted:

As it turned out, much of SB 76 passed. But all of the above, with one exception, is still happening. The exception: Real estate sales are still occurring, driven to a great extent by the migration of 324,000 people into Florida last year.

We should also say some of the provisions of SB 76 have had some positive effects, albeit not much. Sen. Jim Boyd, R-Bradenton, author of last year’s bill, says a few insurers have reported that the way legal fees are now regulated and calculated has curtailed the filing of insurance-claim lawsuits.

But for the most part, the condition of Florida’s homeowner insurance market continues to worsen. Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, one of the Senate’s leading advocates for reforms that would create a rational insurance market, told us this week: “It won’t be long before Floridians’ annual insurance premiums will be more than their mortgage payments.”

Overall, the state of property insurance in Florida is much like the aftermath of a hurricane — a chaotic, costly mess.

A partner of one of the leading insurance agencies in Sarasota told a group of CEOs recently that this past summer his firm received notice from one of the state’s property and casualty insurance carriers that it would not renew 2,000 of this agency’s customers’ homeowner policies. That triggered a mad scramble to notify and secure new policies — in the height of hurricane season. To make the news worse, the new rates were running 30% to 40% higher than what the customers were paying. And that was on top of 10% to 30% increases in 2020.

Insurance carriers, meanwhile, continue to lose massive amounts of money — largely because of lawsuit-driven insurance claims.

There hasn’t been a major hurricane event in Florida since 2017. Nonetheless, the state’s 52 Florida-based insurers reported aggregate losses from 2017 to 2020 of $1.32 billion. In 2021 alone, losses are expected to top $1 billion — another calamitous record.

What’s driving the losses? The lawsuits. They’re expected to reach a record 100,000 lawsuits when final statistics are tallied for 2021 — a 25% increase over 2020. For perspective on the scope of Florida’s insurance litigation problem, consider: In 2013, there were only 27,000 insurance-claim lawsuits. What’s more, while Florida accounts for only 8% of P&C insurance claims nationally, it accounts for 76% of P&C lawsuits in the nation.

That tells you how out-of-whack the situation is.

Guy Fraker, founder and owner of Key West-based Build Any Future Advisory, who has tracked the state’s P&C industry for more than two years, describes Florida this way: “We don’t have an insurance market in Florida. We have a litigation market.

In a 110-page report, “The Dark Side of Insurance Innovation: Florida’s P&C Litigation Economy,” Fraker wrote: “Florida’s litigation economy has grown to an annual revenue stream exceeding $5 billion for the benefit of fewer than 100 people. The funds come through insurers, but not from insurers. This revenue stream is taken from insurance company investors and 9 million Floridians, on an involuntary basis.”

Contractors and trial lawyers essentially have been collaborating since 2018 in a scheme in which contractors comb neighborhoods affected by storms, advertising to inspect homeowners’ roofs for damage. If they find evidence of even a small leak or a few broken tiles, they’ll parlay that into an insurance claim and lawsuit that will result in insurers paying for the full replacement of roofs that need only repairs, plus substantial legal fees.

“The carriers are getting crushed with water damage suits in South Florida, roofs in Orlando and lead pipe damage in older homes all over Florida,” Brandes says.

And while SB 76 has provisions that can help avoid lawsuits (pre-suit communications) and that bring rational calculations to the awarding of legal fees and thereby reduces the incentive to file lawsuits, Fraker told us this week some trial lawyers now have a new tactic to extract large amounts of money from insurers: condominium associations.

“They found a replacement for what they lost from [the new] fee multipliers,” he said.

Fraker has researched multiple instances of lawyers filing insurance-claim lawsuits on behalf of condo associations, using the same strategy as they have in single-family neighborhoods: Find one condo building in a large complex with evidence of damage or a leak, and then leverage that into requiring the insurance carrier to replace the roofs on the entire complex.

Fraker says these suits are referred to as “supplemental condo association claims” — essentially reopening closed cases based on the discovery of previously undetermined damage.

As you can imagine, the dollars involved are much greater than fighting in court to replace a roof on one home.

The fate of now liquidated American Capital Assurance Corp. is a case in point (see sidebar). Lawsuits and losses ultimately led to the liquidation last April of the 15-year-old St. Petersburg-based insurer. American Capital insured 30,000 buildings in six states (2,000 policyholders in Florida) with insured value of $38 billion.

In a 30-day period prior to New Year’s Eve 2019, 50 claims lawsuits were filed against American Capital. Many of the suits were filed by law firms given the assignment of benefits by the policyholders and filed two years after claims previously had been settled. This time, the lawyers were seeking damages 100 to 350 times greater than the original settlements.

American Capital didn’t have the capital to bear the losses.

Altogether, Florida’s dysfunctional property insurance market has costly consequences for Florida homeowners and all taxpayers.

For one, as the number of investor-owned, Florida-based insurance carriers shrinks and continues to weaken financially, this means the supply of property insurance will continue to shrink. As supply shrinks, the cost of property insurance will continue to go up.

“We’re in for a couple more years of paying more for property insurance,” Brandes says.

Which also means housing affordability — already an acute problem throughout the state — will grow increasingly worse. Apartment dwellers are seeing 30% increases in their monthly rents — driven by inflation, the rent moratoria during the pandemic and rising insurance rates. Landlords are cramming three years of increases into one.

Brandes says Floridians who buy new homes won’t have trouble finding and buying property insurance, but Floridians who buy 30-, 40- and 50-year-old homes, especially ones with old roofs, will be forced to pay rates close to or more than their mortgage payments.

A second adverse effect of Florida’s dysfunctional insurance market is how it affects Citizens Property Insurance Co., now the largest property insurer in the state. If you can’t buy property insurance in the private market, Citizens is your last resort.

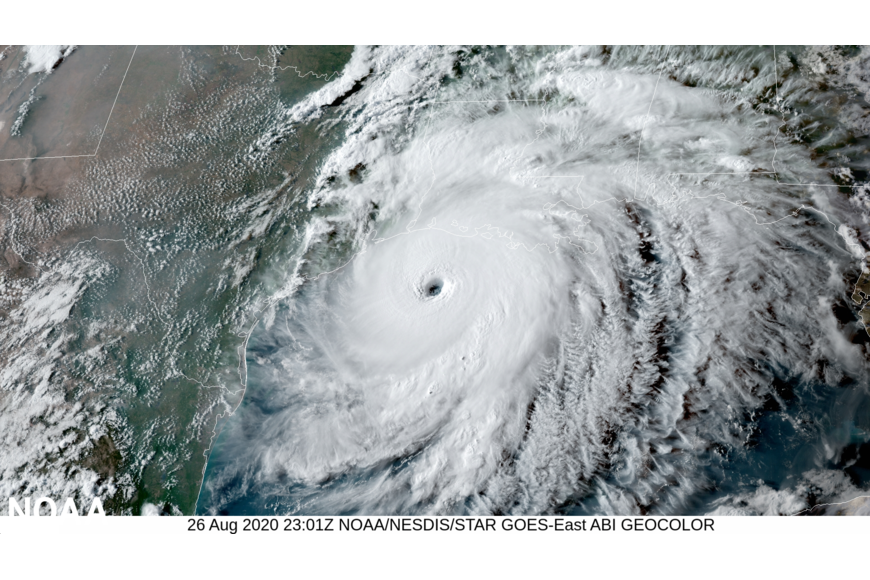

But there is a big catch that most Floridians don’t realize. The more policies Citizens takes on, the greater the risk for Floridians. If a Category 5 hurricane destroys much of South Florida, where Citizens insures 33% of the 1.5 million residential properties, and if Citizens doesn’t have enough surplus and reinsurance to cover the losses, Citizens can assess all Florida insurers, which in turn would assess their Florida policyholders.

In other words, it’s totally not in Floridians’ economic interest to see Citizens Property Insurance grow. It is in Floridians’ interests to see it shrink in the number of policyholders and the value of property it insures.

But that is not happening. In December, Barry Gilway, CEO of Citizens, told his board of governors that because of the shrinking supply of insurers; their reluctance to renew and write new policies; and the continuation of out-of-control lawsuits, Citizens is taking on 5,000 new policies a week.

In his December report to the board, he projects Citizens will grow from 775,431 policyholders at the end of 2021 to 1,064,220 policyholders in 2022, a 37% increase.

Brandes is not optimistic the Legislature has the will to fix Florida’s property insurance market. “It’s all hands on deck, including people waking up who are sleeping under the decks,” Brandes says — his way of saying Florida lawmakers continue to resist changes that would make Florida property insurance an insurance market, not a litigation market.

Sen. Boyd has filed another bill this session, SB 1728, to try to enact changes that would help reduce the roof-replacement lawsuits — changes the House declined to adopt in 2021; and changes that would allow Citizens to be able to move its rates closer to market rates, and thus reduce its exposure.

The House also has a bill, HB 1307, but it doesn’t embrace the Senate’s provisions that would reduce the number of roof replacement claims or allow Citizens to raise rates fast enough to become actuarily sound.

The House bill is no surprise. The trial bar, which has turned roof and water claims into a billion-dollar annual source of legal fees, exerts more influence over the House than it does the Senate.

If Brandes had a magic wand, his fixes would be dramatic — about as close to an unregulated, buyer-beware insurance market as you can get. He described it as similar to what is known as a surplus lines market.

Surplus lines insurers are less regulated and take on risks that other carriers won’t. As such, they are allowed to charge premiums accordingly, typically higher than everyone else.

One of the catches for policyholders is their policies are not backed by the Florida Insurance Guaranty Association, a state agency required to fulfill the policies of license insurers that go bankrupt.

Brandes says property owners and their insurance agents would have to become much more astute about what they’re buying, instead of having the Legislature regulate every aspect of the industry. And instead of the Legislature tilting insurance policies that make lawyers rich. Says Brandes:

“Because of the Legislature, insurers cannot write profitable business in Florida.”

Now there’s a shocker: Government policies are the true source of why your insurance rates will continue to go through the roof.