- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

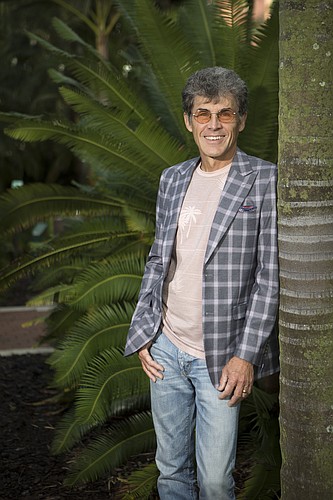

Ken LaRoe doesn’t look, talk or act like a banker. A native of Eustis, a town of about 18,000 people in Lake County, he’s a blue collar, no-nonsense guy with a contrarian streak and healthy sense of wanderlust who started his career as a mechanic and thought he was destined for a career in the automotive industry — before a workplace mishap led him to enroll in community college.

"I thought, 'You know, this is no way to make a living,'" LaRoe says. "'I can't imagine doing this when I'm 50.'"

LaRoe went on to obtain degrees in business and law, and to look at him today, you’d peg him for a college professor — not someone who has successfully founded and sold two banks and now, at age 63, is about to start another one.

“My wife calls me the ‘un-banker,’ and I try to be that to every extent possible,” says LaRoe, who’s based in Orlando but is in the process of launching Climate First Bank, which will fund green initiatives including solar and wind energy, in St. Petersburg by mid-2021. “I tell people I’m a rabid environmentalist, and all the conservatives in the room roll their eyes. And I say, ‘Yeah, but I'm a rabid capitalist too.’ They go hand in hand, contrary to what you might believe. If you're not making money, and you're not prosperous, none of these environmental things are going to happen.”

He adds: “That’s why I think [the environmental movement] has gotten nowhere in banking. There’s just this ridiculous denial of science and facts from conservatives.”

LaRoe realizes he might face skepticism from investors on the model of combining environmental causes with the core of how a bank makes money, off loans. He’s used to it. But he says his previous banks’ track records speak for themselves.

‘As the world increasingly sees how important the environment is, people will more value businesses not just because they’ve done things right but because they’ve done the right things.’ Joel Hunter, longtime friend and business associate of Ken LaRoe

“The banking industry is highly conservative, especially the community bank side of it,” he says. "I personally get a lot of criticism. We've gotten criticism for the position we take, and I'm quite honestly befuddled. I don't get it. A lot of people say, ‘Why would I want to invest in this crazy social scheme or experiment or whatever?’ And I say, ‘Well, we had financial performance in the top 10% of all banks in the state of Florida.’ We didn’t suffer any, that’s for darn sure.”

Yet starting a bank amid a pandemic and a period of consolidation in Florida’s banking sector is no sure thing. And with $17 million already raised for Climate First Bank — which recently announced its flagship location will open in downtown St. Pete, at 5301 Central Ave., in the second quarter — will the third time be just as charmed as the previous two?

REBEL WITH A CAUSE

The iconoclastic LaRoe has a history of rocking the banking industry boat. After selling the first bank he founded, Florida Choice Bank — which he had grown to more than $400 million in total assets — in 2006, he took some time off, even contemplated retirement, before launching First Green Bank, headquartered in Mount Dora, in 2009. He claims it was the first bank in the eastern U.S. with an environmental and social responsibility mission statement at its core while also operating as a traditional community bank. The return on the sale of the bank was 416%, high for a community bank but befitting the mid-2000s boom.

“I wanted to do something that gives back,” LaRoe says, “and I've always been an environmentalist — my whole life. And so I came up with the idea First Green Bank, and we got that charter on Dec. 22, 2008. And it was the last bank charter granted by the state of Florida for nine years. That was the start of the journey, of asking, ‘What does it mean to be a values-based bank?’”

For LaRoe and his investors, it meant success — lots of it. First Green had $825 million in total assets when it was sold to Stuart-based Seacoast Bank, for $115 million, in 2018. The return on that sale was 200%. The bank provided low-interest commercial loans for solar energy projects and provided banking services to Florida’s fledgling medical marijuana industry at a time when many traditional banks wouldn’t countenance cannabis. At one point, LaRoe says, the bank had some $50 million in deposits from companies affiliated with the medical marijuana industry in Florida. It didn't do any medical marijuana loans.

“As the world increasingly sees how important the environment is, people will more value businesses not just because they’ve done things right, but because they’ve done the right things,” says Joel Hunter, LaRoe’s pastor at Northland Church in Longwood and a founding member of the First Green Bank board. “The right things for people beyond their own institutions. People respect that.”

Hunter isn’t involved in Climate First Bank. But he believes LaRoe’s venture will successfully boost the triple bottom line — people, planet and profits — that socially conscious businesses are increasingly using in their plans and strategies.

“If Ken is heading it up, people are going to be better off for it,” Hunter says. “I'm never surprised that Ken wants to do something to better himself and the community. He has too much energy to sit around. He’s got to have a mission.”

Hunter says not everyone will agree with LaRoe’s beliefs and views, but that’s OK. Much like other influential business leaders who don’t necessarily embrace conventional wisdom, you have to look at the whole picture.

LaRoe, he says, “is very passionate and very opinionated. You never have to wonder where he stands on anything. There’s no dial in the guy. But he’s also a great business person who cares about people deeply. He cares about his impact on the environment, improving the community and business being good for everybody. He also has a great sense of fairness and roots for the underdog.”

A-HA MOMENT

For LaRoe, inspiration for First Green Bank and, now, Climate First Bank came while he was briefly retired from 2006 to 2008. He had sold Florida Choice Bank and was tooling around the country in a RV with his wife, Cindy. During their travels, LaRoe read the book “Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman,” by Yvon Chouinard, the outdoorsman and environmentalist who in 1973 founded Patagonia, a clothing and equipment company based in Ventura, Calif.

Patagonia has become widely noted for its environmentally and socially responsible business practices. It was one of the early members of the global B Corp movement, which advocates for businesses to become a force for good, not just profit.

“I read that and thought, ‘Well, that's what I want to do,’” LaRoe says. “I want to do something more than just make a bunch of people money. I want to do something that gives back.”

The B Corp movement is thriving in St. Petersburg, with companies like Jared Meyers’ Salt Palm Development leading the way. Salt Palm, Florida’s only Certified B Corp property development firm, has been building eco-friendly housing in the Sunshine City. It donates 1% of its revenues to environmental causes and at least 50% of its profits to the betterment of St. Petersburg and Florida. The company’s presence in St. Pete, actually, is one of the reasons LaRoe chose to launch Climate First Bank there.

Meyers, LaRoe says, has become a “change agent” in the city’s property development space. St. Pete Mayor Rick Kriseman has also been an ally.

“He was very encouraging for us to come there,” LaRoe says of Kriseman. “I think the value proposition will play very well [in St. Pete]. It’s a good market, and there’s just not a lot of community bank competition, especially with Freedom Bank just being bought by Seacoast. It just made a lot of sense.”

Competition, or lack thereof, is another key component of LaRoe’s strategy for Climate First Bank. He says the rapid consolidation of Florida’s banking industry in the past several years — with Gulf Coast institutions like Freedom Bank, USAmeriBank and C1 Bank being acquired — actually helps his cause.

“The best thing that can happen to us is for a community bank to get bought because their customers are almost universally abused,” he says. “They want to have the service they love that they got from the community bank. Every time [an acquisition] happens, we always gain a bunch of customers, and that's probably going to keep happening. The number of banks in the U.S. has gone from 14,000, some odd, to 4,000, some odd, since 1980 — it's been a bloodletting of community banks.”

LaRoe’s business plan calls for Climate First Bank to open its inaugural location by May 2021, with another branch to follow in 2022. The goal, he says, is to have branches all along the I-4 corridor within five years, and then to expand out of state to markets such as Asheville, N.C.; Austin, Texas; and Atlanta. Financially, he expects the bank to have $170 million in total assets by the end of its third year in business.

Unlike his other banking ventures, LaRoe intends for Climate First Bank to stick around and not be sold to a larger regional or national bank.

“I'd like to build this one to last, not be built up to be sold,” he says. “That’s the Florida banking model: You build it up, you sell it, the investors make a lot of liquidity, and you move on. But I don't want to do that on this one, if at all possible. I'd like to take it public and then pay dividends.”