- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Turn on the tap in your kitchen or bathroom. What happens? Water comes out.

But for one-fifth of the world’s population — 2 billion people — that’s not necessarily a given.

AquaVenture, incorporated in the British Virgin Islands with a domestic office in Tampa, trying to do something about the growing scarcity of water worldwide — and in the process gain market share in the $4 billion global desalination market.

Founded in 2007 by Doug Brown, AquaVenture — via its subsidiary Seven Seas Water — specializes in water desalinization, purification and delivery for public- and private-sector clients around the world.

The company’s other division, Quench, also deals in water, but in a more familiar delivery system: point-of-use dispensers — that's a water cooler — found in some 40,000 offices and institutions across the country, including half of Fortune 500 companies.

Together, the two lines of business brought in $121.2 million in revenue in 2017 for the publicly traded AquaVenture, which employs 600 people, about 70 of whom are based in Tampa. Revenue, through the company's pioneering Water-as-a-Service model, are up 21% since 2015, when it had $100.3 million.

The flip side to the revenue growth: providing water is a costly venture. The company has posted negative earnings at least three years in a row, including a loss of $41.8 million in 2015 and $25.8 million last year, according to Securities and Exchange filings. A chunk of the losses, nearly $90 million combined over three years, records show, stem from capital expenditures. Investors have shown patience with the company, (stock symbol: WAAS) where the stock has hovered around $14 a share lately, in the middle of its 52-week high and lows.

Brown, in an email response to questions about the negative earnings, says the losses were "driven by non-cash expenses," including stock based compensation. He adds that revenue, with a compound annual growth rate of 10%, were reinvested in the business to "keep propelling growth," which further pushed down earnings. Brown also points out the company has a positive earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, or EBITDA, which was $15.2 million last year, records show. That, plus positive cash flow, says Brown, helps "support our long-term strategic goals."

ESSENTIAL SERVICE

While the company has led a somewhat quiet existence, at least in terms of business media, AquaVenture’s Seven Seas Water division made headlines in March when Brown rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange in recognition of UN World Water Day. It was an effort to raise awareness of water scarcity and how access to water has become a source of political controversy and armed conflict as shortages pose threats worldwide.

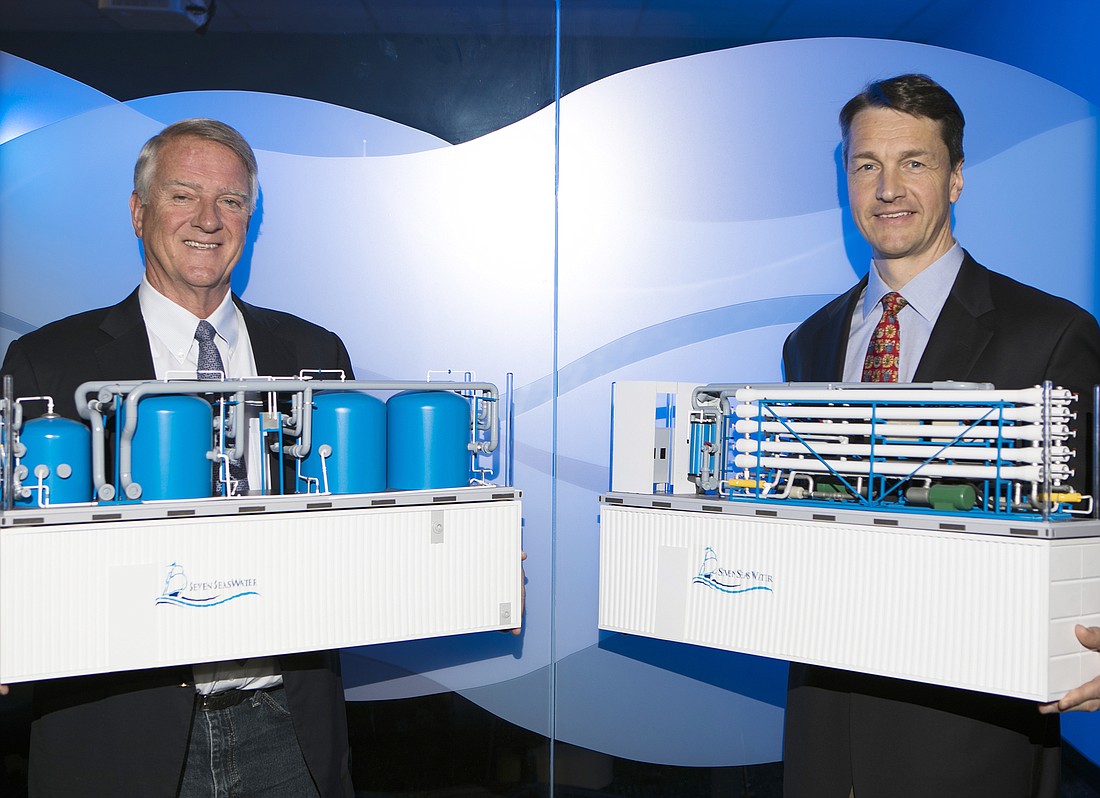

The day at the NYSE was also something of a celebration of one of the company's best achievements. Seven Seas Water has near-perfected the art of logistics by designing a modular reverse-osmosis water desalination plant that costs $750,000 to build — plus an additional $350,000 to $500,00 to install — and can fit inside a shipping container and be up and running within a few weeks. Fully functional, the modular plant can produce 250,000 gallons of potable water per day. These plants have become the company's revenue base.

“What we worry about is the growth rate — how fast can we add more assets?” Doug Brown, CEO of AquaVenture

Not only are the modular plants easy to ship and set up, they’re also resilient. Brown says the company suffered only about $1 million in damages last year from Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria. “These plants are bunkers,” he says, adding that Seven Seas has several of the container-size plants on standby in Miami to quickly respond to water emergencies, but they will also build and acquire larger plants.

Brown says he came up with the idea for the company in 2006 while taking a year off, due to a noncompete agreement, following his departure from Ionics (now known as Puronics), a water filtration systems manufacturer that was acquired in 2005 by GE Water and Process Technologies.

He brought some deep-pocketed investors — including flamboyant billionaire Richard Branson — on board, and built and acquired a few desalination and wastewater treatment plants in the Caribbean. He targeted governments that sometime struggle to provide enough potable drinking water to its citizens, as well as manufacturers and other companies that require regular access to large amounts of water.

“The Caribbean was a great place for us because most of these islands, they just don’t have the water,” Brown says. “They don’t have the capacity to catch the rainwater, and they don’t have any other alternative but to turn to the ocean. Also, they rely on tourism, and they figured out a long time ago that if somebody’s going to pay $300 a night for a hotel room, they want to be able to take a shower, be clean, flush the toilet and brush their teeth.”

GROWTH MODE

Expanding the company’s global footprint has been and remains the biggest challenge, says Brown, who adds there are only about 20,000 water desalination plants around the world. Also, because it’s so essential to everything, the market price of water is usually well below the cost of providing it, which means it is nearly impossible for AquaVenture to boost revenue through price hikes.

“When we get a customer, you keep them,” he says. “It’s a very predictable business. But what we worry about is the growth rate — how fast can we add more assets?”

Seven Seas Water operates nine plants in the Caribbean, one in Peru and one in Chile, and it is bidding to acquire a facility in Ghana, which would represent the company’s first foray into Africa. That deal is expected to close by the end of the second quarter of 2018. Domestically, the company is looking at opportunities in Texas.

The majority of the Seven Seas’ clients are governments or government-run utility companies. It has become the primary water supplier to the U.S. Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands and Dutch St. Maarten. Brown says the company is looking to acquire underperforming plants in South America, the Philippines and Africa, rather than build new facilities that can cost anywhere from $20 million to $50 million. A couple of years ago, he brought onboard Olaf Krohg, an expert in mergers and acquisitions, to serve as vice president of Seven Seas Water as it gears up for growth.

“We are spending a lot of time turning rocks to look for acquisition opportunities,” says Krohg, 56. “There are so many industries that need water, whether it’s the extraction of copper mining through to making cars or electronics or beer. Everybody needs water.”

None more so, perhaps, than the people of Cape Town, South Africa, a city of 4 million people that since 2015 has been hit by a drought that has led officials to limit water use to 50 liters — a little more 13 gallons — a day per person. City officials have issued dire warnings about “Day Zero, the day Cape Town’s taps run dry. It could come as soon as May 11.

“There are a lot of people in Africa who don’t have access to water,” says Brown. “That’s going to be an interesting opportunity.”

Opportunity seemingly abounds everywhere, which is why Brown says it's a good time to be in the water business. He says AquaVenture projects its 2018 revenue to be in the $131-$136 million range.

“The world is getting drier,” he says. “If you look at the period from 1950 to 2000, the world population increased by 40%, and total water consumption, not including agriculture use, increased by something like 400%. So it’s huge that we’re using a lot more water per capita … that creates your existing water crises. Supplies can only go so far. You can’t pump more out of the well because you’re going to dry it out.”

But AquaVenture has to be judicious about where it decides to set up shop. Brown says the company has turned down potentially lucrative opportunities in countries — he mentions Libya and Turkey — that look like solid bets on the surface but are riven with political unrest and terrorist activity. AquaVenture, he explains, isn’t looking to build or acquire a desalination plant for short-term gain. It wants to become an integral part of the communities it serves.

For that reason, AquaVenture hires as much local staff as possible in far-flung locations, and it doesn’t clean house with massive firings or layoffs. Some of the jobs at its plants require advanced engineering knowledge local candidates might not possess, so it will export staff from Tampa or one of its other locations. Plant managers tend to be people who have run Seven Seas facilities in other locations, and the company likes to rotate management personnel around its Caribbean locations frequently so they get a good sense of the different challenges facing the various island nations.

“We have a good solid crew of individuals we can plug in to different places,” says AquaVenture Senior Vice President Thomas O’Brien, who oversees operations. “Every plant is a little bit different, so it’s great cross-training to move employees around. During the hurricanes, we moved a lot of people around.”

HELP WANTED

Talent acquisition is a constant challenge, but the University of South Florida, where AquaVenture has a corporate ambassador, has proven an excellent pipeline of skilled workers — and the company has come up with an innovative way to bring them aboard.

Dave Starman, for example, has shot up the ranks since gjoining Seven Seas Water in 2008 right out of school. Starman, Seven Seas Water’s regional manager for the Virgin Islands, says he started out in the company’s “farm system” before getting a shot at overseeing a plant.

“We go out and look for talent and hire them ahead of having a dedicated role for them, and we assign them to a plant,” O’Brien explains. “The idea is to train them at the plant.”

Starman learned about reverse-osmosis membrane technology — AquaVenture’s stock and trade — during his engineering studies at USF, so landing a job with Seven Seas Water was a welcome way to begin his career.

A decade later, he’s still with the company. Starman calls the work “challenging and rewarding,” and says he enjoys “being the guy who makes the water that everyone drinks … that sense of having an important social function has been a nice feeling.”