When the music played, '50s swing to slow crooners, Nathan Benderson just couldn't help himself. He would always get up and dance.

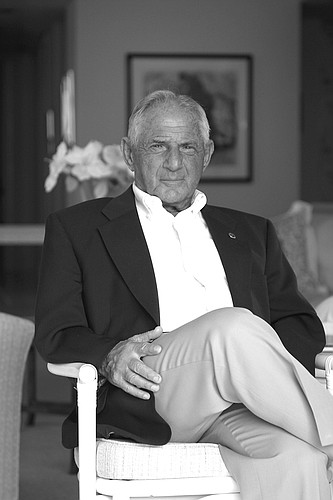

The patriarch of one the region's most charitable families and successful businesses, Benderson lived like that well into his 90s, say several in his large network of family and friends. Many in that network cited Benderson's wit, business acumen and humility — in addition to his dancing skills — this week in remembering him. Benderson died April 7, after a brief illness. He was 94.

“Everybody who had a chance to meet him will never forget him,” says Rob Oglesby, president of Honor Animal Rescue in east Manatee County, one of the numerous charities Benderson supported. “He was one of a kind.”

That goes from nonprofits to business. In his work with nonprofits, Benderson championed a range of causes, from the elderly to the poor to animal rights. Jewish-related causes were also important to Benderson, who took 14 trips to Israel in his life.

In business, meanwhile, Benderson, a native of Buffalo, N.Y., was at the helm of Manatee County-based Benderson Development for nearly 60 years. The firm holds a massive portfolio of shopping malls, industrial buildings, office parks, hotels, housing communities and land. Benderson Development's holdings encompass 35 million square feet spread through nearly 500 properties in 38 states.

Benderson's niche, however, was his ability to turn around underperforming properties. Indeed, in a Jan. 1, 2000 story, The Buffalo News called Benderson a “pioneer in the shopping center industry and a pivotal force in western New York.” The paper named Benderson one of the 20th century's top business personalities.

That personality resonated with Sarasota-based developer Wayne Ruben, who partnered with Benderson on dozens of projects. Ruben fondly recalls driving around Florida with Benderson, chatting about business and families. “He was a terrific mentor, and he was brilliant guy,” says Ruben. “He was like a second father to me.”

Ruben says Benderson had the uncanny ability to look at a property and calculate financial projections on the back of an envelope within minutes. The numbers, says Ruben, nearly always panned out precisely the way Benderson predicted.

Like many others who knew Benderson, Ruben has another lasting memory of Benderson: his thrift, and sense of consistency, especially when it came to eating out. Ruben ate lunch dozens of times with Benderson, and their go-to spot was the Subway inside the Mobil gas station at Lakewood Ranch on University Parkway. The pair would always split a foot-long turkey sub.

Ruben was also part of a small contingent of Benderson confidantes who got together to buy the developer a Rolls Royce for his 85th birthday. Ruben and Benderson's sons presented the car to Benderson at a dinner celebration at the Colony Beach & Tennis Resort on Longboat Key.

Benderson, who could have a gruff side, grudgingly accepted — though he always preferred more practical and economical vehicles, like his Ford Taurus.

A product of the Great Depression

Benderson's frugality is likely connected to his youth. Called Sonny by childhood friends, Benderson saw his family's business devastated by the Great Depression. His father, Isaac, owned a company that found and sold broken glass. Benderson worked there during the summers, sorting broken glass soda bottles by color.

“I realized what it was like not to have anything when my parents lost their home when the stock market crashed,” Benderson told the East County Observer in a January 2009 story. “I was eager to find different ways to try to help my family get along and survive.”

By the time he was 16, Benderson had dropped out of high school and founded his own business, the Bison Bottling Co., which bought and sold used bottles to dozens of beer breweries in Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, and other New York cities.

At the age of 18, he was making more money than his father. He gave his father $500 for the down payment on a house.

By the time Benderson was 21, he had two companies — the bottling business and a root beer brewery. He worked around the clock to make it work, often sleeping in the back seat of his car.

Benderson bought his first property when he saw consolidation shrink the beer business into fewer breweries. He decided to try to buy at a courthouse auction the plant of one of his former customers, the shuttered Schreiber Brewery.

With three other partners, himself putting up about 62.5% of the $27,500 down payment needed, Benderson made his first real estate deal. The bankers holding the mortgage on the property were surprised to learn, however, that Benderson couldn't pay off the full $275,000. Instead, he asked them to continue holding the mortgage and, as he told the Business Review in a 2001 interview, he convinced them he knew enough to be able to pay off the note.

Benderson made good on his promise. Working furiously to rehab and lease the building, he paid off the note in 18 months — 4.5 years before it was due.

Benderson sold off machinery and metals, leased unused space and generally found anyway he could to make money off the brewery purchase. The acquisition was the genesis of Benderson Development.

As he grew his portfolio, Benderson financed his deals with second mortgages on existing properties and borrowed cash from individual investors. However, he told the Business Review he was always careful not to become over-leveraged. “Don't buy what you can't afford,” he said.

Benderson had a few other rules he followed in his deals: Don't get involved in businesses you don't know; don't build monuments to yourself; and build equity, don't sell.

Giving back

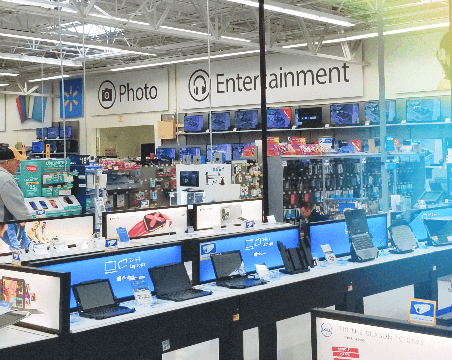

Benderson Development, after decades of success in Buffalo, relocated to east Manatee County in 2004. It bought the Sarasota Outlet Center, a struggling property just west of the University Parkway exit of Interstate 75. The company paid $6 million for the center, which it has since turned into a thriving business hub, the University Shoppes. Tenants include Bonefish Grill, Pei Wei Asian Diner and Marshalls. Benderson's corporate headquarters is also in the center.

The business success allowed Benderson to focus on charitable endeavors. It was in one of those endeavors, at the Sarasota-based All Faiths Food Bank, where Benderson met and befriended Rabbi Brenner Glickman of Temple Emanu-El in Sarasota. Glickman chairs the capital campaign for the food bank, where he saw Benderson's commitment to people in need.

“He was a tough man, and he could be famously gruff,” says Glickman. “Yet, when he spoke of people in need, he would always get emotional. I am so grateful for all the kindnesses that he showed me, personally. I miss him already.”

Benderson is survived by his wife, Dora Benderson, three sons, eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. He's also survived by longtime companion Anne Virag. A funeral service was held April 11 in Buffalo. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that contributions be sent to the Jewish Community Center of Greater Buffalo, 2640 N. Forest Road, Getzville, N.Y., 14068 or Honor Sanctuary Animal Rescue, 8435 Cooper Creek Blvd, University Park, Fla., 34201.

DON'T BUY GREEN BANANAS

From philanthropy to business, many who knew Nathan Benderson call him a mentor, with an infectious humble and hardworking approach to life.

One lesson more than a few learned from Benderson: Never procrastinate. Do your research, but when it's time to do a deal or a job or a project, don't put it off.

Rob Oglesby, president of Honor Animal Rescue in east Manatee County, which Benderson supported, recalls it this way. “One of my favorite memories of him,” says Oglesby, “was he always said, 'I don't buy green bananas.'”

Translation: Benderson didn't buy non-ripe bananas because he didn't want to wait for them to ripen.

HOLIDAY RITUALS

Nathan Benderson fell ill a few days before Passover, one of the most significant Jewish holidays. He died April 7, the first full day of the holiday, which lasts for eight days.

Still, on the eve of his death, Benderson's family and a few close friends were able to have one last Passover Seder together. The Seder is a ceremonial dinner that marks the beginning of the holiday. This Seder was held during sunset April 6 in Benderson's room at Sarasota Memorial Hospital, where some of the Passover food staples — matzah, gefilte fish and charoses — were shared.

Benderson died early the next day.