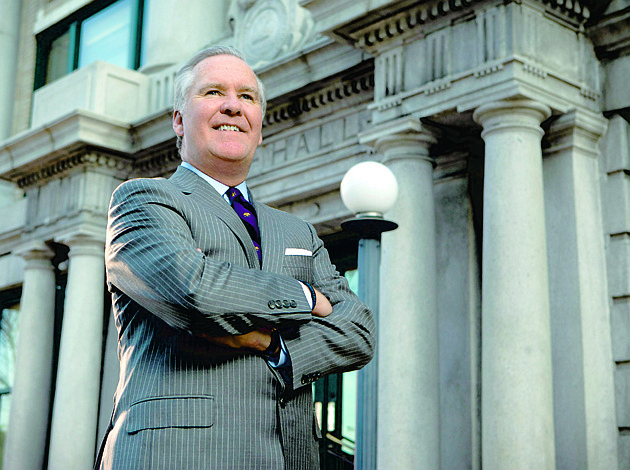

As he approaches his second anniversary in office, Mayor Bob Buckhorn has already led a fruitful effort to bring fresh residential development to downtown Tampa after the lean years of recession.

He has invigorated the arts district and seen the Riverwalk pedestrian project become reality 40 years after preceding mayors first envisioned the corridor. But that's just the start.

Buckhorn has miles to go, in his view, as he seeks to transform Tampa into an economic powerhouse and a more dynamic place to live. His hardest challenge is to find a way to keep bright young people from abandoning the city, to bring them back once they set off for universities in cities that offer the jobs and pay scales for which they have been educated, and the stimulating nightlife that keeps them absorbed after hours.

“I really want to transform Tampa from a city that has been losing its best and brightest kids to places like Austin, Charlotte, Raleigh-Durham and San Diego, to a city that can compete with any of those for the best talent in the country,” says Buckhorn. With an unemployment rate of 8.5% the city is ripe for a turnaround. For at least a decade, Tampa Bay has suffered a brain drain and disruption of generational ties, as the grads took technology, finance or medical positions elsewhere in the Sun Belt. “It's been a one-way street,” the mayor says. He is determined to bring the grads home.

Buckhorn was elected mayor of the city of 346,000 in 2011, but he is no newcomer to Tampa's economic issues, or its politics. In the 1980s, he coordinated the mayoral campaign of Sandy Freedman and became the mayor's special assistant after her election. He has done his due diligence, serving on the city council and on planning and public safety committees. In the '90s, he fought for years, as a committee chairman, to save MacDill Air Force Base from closure. As of 2011, the base generated 6,400 jobs and an annual economic impact across Tampa Bay of $2.1 billion, according to the base comptroller.

At the halfway mark of his four-year term, Buckhorn champions a handful of causes to promote economic and cultural growth. In addition to focusing on downtown improvement, welcoming multifamily and other ground-up development, he encourages innovation, startups and the creation of high-paying, high-tech and finance jobs. Those goals, and Buckhorn's energetic approach to stimulating change, have brought the mayor, a Democrat, many Republican as well as Democratic supporters.

“He has brought energy to the city. He's not sleepwalking through the job, he's getting things done,” says Bill Eshenbaugh, a commercial real estate broker and developer who first met Buckhorn in the 1980s when he was a lobbyist for the builders association. “We respect him, and respect the job he's doing.”

But Buckhorn doesn't promote growth at any cost, says Tampa attorney Ron Weaver. “He has been one of the nation's top mayors for bringing responsible development,” the attorney says. “He knows how to say no if he feels a project is not sufficiently responsible.”

In Tampa, a litany of developments and property conversions are stirring optimism. Developer Punit Shah's new Aloft hotel on Kennedy Boulevard, a planned $85 million, 30-plus-story apartment tower by developers Greg Minder and Phillip Smith near the Straz Center for the Performing Arts downtown, and a Bayshore multifamily development are all in the works.

And more projects are pending. “We've got a lot of folks kicking tires,” says Buckhorn. The proposed projects are mainly high-rise residential, the property type lenders currently are financing. In an encouraging market turnaround, planners report great demand for downtown rental units. “Demand is much greater than the supply at this point,” the mayor says.

Across the country, downtowns have become a destination of choice, as young professionals and baby boomers alike opt for walkable, culture-rich neighborhoods over suburban lifestyles. The desire for urban living is particularly evident in Tampa, Buckhorn says. He predicts that within four or five years, growth will transform downtown Tampa.

The Riverwalk, designed to connect the performing arts center and museum to hotels, parks, restaurants and, eventually, the Channelside district, is slated for completion in 18 months. Studies show that newcomers gravitate to walkable cities with cultural amenities. “A decade ago, there were about 700 people that lived in downtown Tampa — 400 of them lived in jail,” Buckhorn says with a laugh. Now, thousands of people live in downtown and nearby condos and apartments.

Linking both sides of the Hillsborough River with pedestrian improvements is important to the renaissance, Buckhorn says. “Tampa had turned its back on the waterfront. What we're trying to do is make the water the center of our downtown, not the western edge.” Another reason for incorporating the west bank is that the University of Tampa is an important economic engine for the city.

Gateway City

Buckhorn also envisions Tampa as a gateway to Latin America. He has traveled to Colombia and Panama to foster trade and encourage airlines to establish direct flights to Tampa. In the mayor's view, it makes sense to strengthen transportation links with the Americas. Colombia is Florida's second-largest trading partner. The U.S. Commerce Department reports that the state exports more than $2.5 billion in goods annually to the Latin country, from metal gaskets and electrical parts to orthopedic devices.

About a third of the state's 300,000 Colombian residents live in Tampa Bay, and both Floridian and Columbian businesses have current and potential clients in each country. Moreover, Tampa could serve as a financial center for wealthy clients and businesses from Venezuela and nearby countries looking for a safe harbor for their funds amid political and financial uncertainty, says Buckhorn.

For years, Venezuelans put their wealth in Miami institutions, and Brazilians have bought condo projects there at bargain prices. “Miami is increasingly more dysfunctional from a business perspective,” however, says Buckhorn. “Because of security [issues], it's a tough place.” The city's airport is not as easy to navigate as Tampa's, he says, and Tampa Bay is better located as a distribution point for goods being shipped to the southeastern U.S. “We are the very sensible, cheaper, less complicated, less corrupt, alternative,” says Buckhorn.

Buckhorn supports transportation links closer to home, as well. He favors construction of a rail link from downtown Tampa to the airport. It would make sense, also, he says, to link the transit system to employment centers. They include the University of South Florida, the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, and M2Gen, a service company undertaking research in a collaboration between Moffitt and the pharmaceutical company Merck & Co.

However, in 2010, before Buckhorn took office, Hillsborough County voters said no to a sales tax increase that would have funded the light rail line. Across the bay, Pinellas County is considering its own light rail project, along a 24-mile stretch from St. Pete to Clearwater.

A missed opportunity?

As he seeks to attract high-paying jobs, Buckhorn says Tampa may have missed opportunities over the years, as the city encouraged real estate development, retail growth and tourism, but placed too little emphasis on attracting financially strong institutions and firms whose employees could afford upscale apartments or condos.

He remembers when officials from Charlotte used to travel to Tampa “to see how we did things.” Not anymore. Charlotte became a major banking and finance destination, he points out. “It transformed itself from a sleepy little redneck town to the financial capital of the South.”

But he's not discouraged. “We could do the same thing,” Buckhorn says. “A large part of my mission is to inspire people to believe that we can be better, that we can do more, that we don't have to settle for second best.” Attracting call centers, restaurants and retail stores isn't enough, he says.

The city has to be more strategic as it rethinks its economic strategy, the mayor believes. “My kids are not coming home to a call center job. Nor should they, because that doesn't create real wealth.”

And that leads him back to his main challenge. “Even though my kids are young, that they come home here to raise their families. Then I will have succeeded in creating that environment that will attract the best and the brightest. Not just my kids, but the community's kids, and others from around the country that want to come and be a part of this.”